A critical note from the author – The USS Mako, depicted in Sea of Betrayal, is a fictional US Gato-class submarine. Her hull number was originally assigned to the USS Goldring, whose build was canceled in 1944. Her crew and officers, along with her top-secret orders, are solely the invention of the author’s imagination.

That said, the USS MAKO is meant to represent the bravery and heroics carried out by the men of the US Submarine Service, not only during World War II, but in their continuing service to the US Navy today.

The following post is a brief description of the Gato-class submarines, which, along with the enhanced Balao-class, had a larger impact on the outcome of the Pacific War than any other type of American warship.

The Legacy of American’s Gato-Class Submarines

World War II was the most significant conflict in human history and was unparalleled in its scope of destruction, tragedy, and sacrifice. Unfortunately, like all wars before and since, it was also a testbed advancing military technologies at an unprecedented speed and a remarkable scale.

While the war raged on multiple continents, some of the most critical battles were fought beyond the horizon. As they had faced in the Great War, the world’s navies were confronted with a multi-dimensional battlefield. But by the start of WWII, submarine warfare had evolved from shallow-running vessels that surfaced to exchange cannon fire into swift predators able to deliver a lethal spread of fast-moving torpedoes.

There is little argument that surface ships bear the brunt of naval warfare, yet the submarine proved itself one of the deadliest weapons of WWII.

At the forefront of these silent hunters were America’s Gato-class submarines, whose design, capabilities, and contributions greatly tipped the war in the Allies’ favor.

A Bit of History

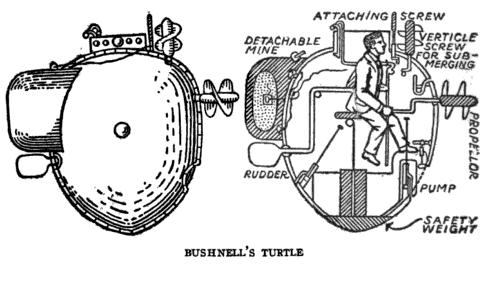

Surprisingly, America’s trials with underwater warfare dates to the Revolutionary War. Built by American David Bushnell in 1775, the first submersible designed for battle was the Turtle, a one-man craft driven by a simple hand-powered propeller. This primitive vessel, looking like an oversized barrel, was designed to slip beneath British ships at anchor and attach an explosive charge. While the Turtle’s clandestine assaults failed, she revealed how easily a stealth craft could approach an unsuspecting enemy.

By World War I, submarines had become more sophisticated, but many of their engagements were on the surface as torpedo technology was in its infancy and unreliable. Still, the ability to approach an enemy ship by stealth brought a new dimension to sea battles.

It might be said that it was the limited impact submarines showed during WWI or a misunderstanding of the sub’s potential in a war theater that led the commanding ranks of Japanese Navy to make a critical mistake during their surprise strike on Pearl Harbor.

Japan's Lethal Mistake

The Imperial Navy attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. This first-strike strategy was designed to weaken US naval strength and prevent the United States from interfering with Japan’s conquest of Southeast Asia.

During the two-hour attack, Japan’s warplanes focused primarily on America’s massive warships moored along “battleship row.” By chance, the aircraft carriers assigned to Pearl Harbor were at sea on maneuvers and thus saved from the assault.

But the Japanese pilots overlooked another class of warship during their surprise attack: America’s Gato-class submarine.

With just 21 submarines stationed in Hawaii and only four in port the morning Yamamoto’s planes attacked, it is almost understandable that the submarine force was overlooked. This miscalculation, however, would haunt Japan’s military strategists for the rest of the war.

Thrust into a Pacific conflict with most of its frontline battleships either severely damaged or destroyed; it was the U.S. submarine force that was first able to take the offensive against Japan.

Designed and Constructed Out of Necessity

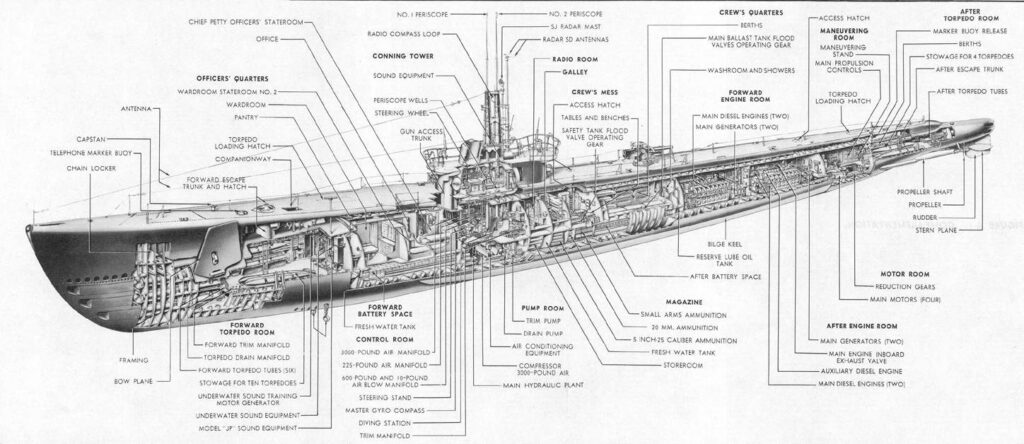

Designed to patrol the vast expanses of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, the Gato-class submarines represented a significant leap forward in submersible technology. With a length of over 300 feet and a displacement of more than 1,500 tons, the Gato-class subs were larger and more capable than their WWI predecessors. Powered by diesel-electric engines, they could travel at speeds of up to 21 knots on the surface and 9 knots submerged. Armed with torpedoes, deck guns, and anti-aircraft weapons, Gato-class submarines posed a formidable threat to the enemy.

Tight Quarters

With limited space and resources, life aboard a submarine was both challenging and demanding. Crew members endured cramped conditions and long patrols. Not only were they living in a war zone, but they were faced with the constant threat of mechanical failure and underwater unknowns.

Prowling the depths for enemy targets, the crew member understood and accepted these threats. As with other branches of the military, this built a deep sense of camaraderie. Crew members learned to rely on each other for support, strength, and the knowledge their contribution to the war effort was unique amongst the navy personnel.

The Gato-class submarines, along with the similar, but more capable Balao-class submarines, were instrumental in shaping the outcome of World War II. They played a critical role in securing victory, not only by directly attacking the enemy’s warships but also disrupting the flow of arms and supplies to their island bases.

At Sea

In the Pacific Theater, Gato-class submarines played a crucial role against Japan. While they engaged merchant ships as a means to disrupt supplies lines to Japan’s island bases, the crews of these silent hungers were primed to fight on the frontline against the enemy’s most fearsome warships.

Even though the submarine force represented only 1.5 percent of the U.S. Navy, ultimately, America’s silent service would destroy 1,314 naval vessels in the Pacific, including eight aircraft carriers, a battleship and 11 cruisers. They would sink 1,200 merchant ships carrying nearly 5 million tons of supplies, which is estimated to have been 60 percent of Japan’s merchant losses.

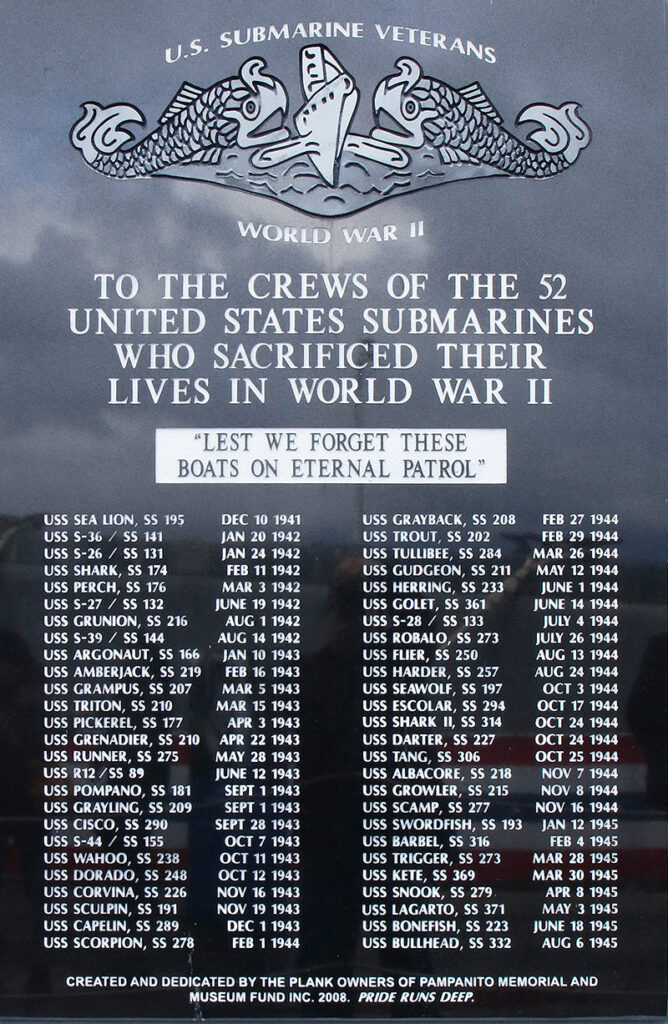

Eternal Patrol

The legacy of America’s submarine service during WWII will always stand out in the annals of U.S. Naval history. Through museums, memorials, and commemorations, the members of this elite force will always be remembered and honored for the sacrifices they made.

“Lest we forget these boats on eternal patrol.”

To the 375 officers and 3131 crewmen of the 52 U.S. submarines who sacrificed their lives during World War II. The passing years have not diminished your gallantry nor lessened the gratitude our country owes you for your sacrifice.

Further Reading