A Tale of Discovery, Loss, and Legacy

500,000 YEARS AGO

In the annals of paleoanthropology, few discoveries rival the significance and intrigue of Homo erectus pekinensis… The Peking Man.

Their story leads back over half-a-million years when small troupes of humanoids, a subspecies and distant relative to modern man, roamed the forested foothills of a vast yet unforgiving landscape. To a creature still evolving its mental capacities and with a low ranking on the predatory scale, the world must have seemed a malevolent place ever eager for their demise. It is little wonder why they sought the safety of caves and alcoves. Yet, without the ability to speak and with only a feeble control over fire, our distant cousins nevertheless managed to survive as a species for nearly 1.5 million years.

DRAGON BONE HILL

Leap forward to 1921 CE, when Austrian paleontologist Otto Zdansky followed his colleague, Swedish archeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson, to Zhoukoudian, China. Andersson had recently discovered an intricate limestone cave system in an area known as Dragon Bone Hill. Inside, he found quartz samples that were not consistent with the cave’s mineral composition and suspected they had been introduced to the underground labyrinth by prehistoric man. Soon after, Andersson arranged for Zdansky to explore and excavate the caves.

The first significant discovery by Zdansky was an unusual fossil molar. As small as this finding was, it justified further investigation. Conditions in this region of China were primitive with scientist having to travel by mule between Beijing and the excavation site. But with the possibility of uncovering a new subspecies of Homo erectus, other anthropologists soon joined the team.

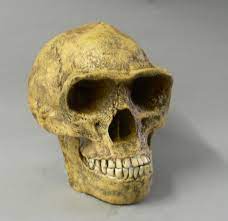

The first humanoid skullcap was discovered in 1929 in a deep crevasse by Chinese anthropologist Pei Wenzhong. A second skull was unearthed the next year, and by 1932, the excavation of Dragon Bone Hill had hosted several world-renowned scientists and over 100 workers from nearby villages.

QUIET FIRE STARTERS

Ultimately, the team would unearth 45 individuals from the cave’s fissures and caverns, along with primitive flake and chopping tools. It is believed Peking Man’s environment was mainly forested and filled with a rich array of flora and fauna. From recovered stone tools, such as scrapers and choppers, anthropologists speculate this subspecies of Homo erectus may have been capable hunters, made clothing, and had the ability to control fire. Other investigators, however, point out that the exact chronology of the cave’s inhabitants is unclear and require further research and debate.

THE FOUNDATION OF CHINESE

ANTHROPOLOGY

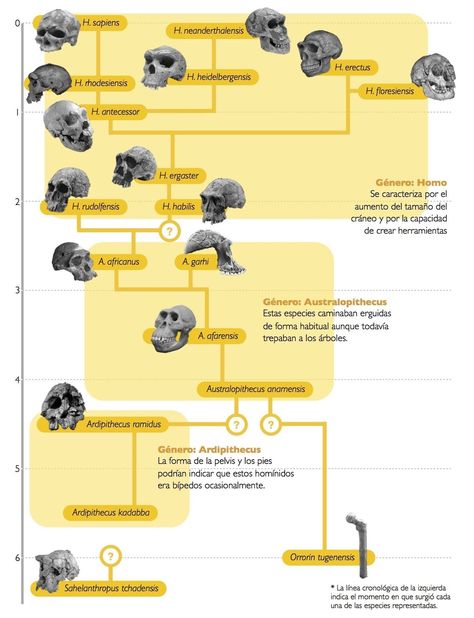

The discovery of the Peking Man fossils was instrumental to the foundation of Chinese anthropology studies and, over time, became a point of distinction for Eastern cultural studies. Even before the fossils were properly categorized on our family tree, Chinese academics placed the Peking Man at the center of an ‘Out of Asia’ hypothesis that stated humans have evolved in Asia instead of Africa.

However, current research and DNA evidence suggest the ‘Out of Africa‘ hypothesis is the more accurate theory and that all modern humans stem from a small group of our ancestors who made their way from the African continent some 2,000 generations ago.

Still, at the time of their discovery, the Peking Man fossils became an important symbol of the Chinese people and their long cultural heritage. The jubilation over this new discovery, however, was soon overshadowed by the growing threat of war. In 1937, forces of Imperial Japan continued their aggression across northern China and advanced on Beijing. With the invasion spreading, the decision was made to safeguard these precious relics.

THE FOG OF WAR

In a daring operation, the fossils were packed into wooden crates and sent to the port city of Tsingtao in the Shandong Province. From there, they would be smuggled aboard a US Navy ship to America.

Tragically, fate had other plans. On December 7, 1941, the day Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and drew the United States, the enemy forces also pushed further into China, and Tsingtao came under Japanese control. From that day, the fossils were lost in the chaos of war.

THE MYSTERY AND LEGACY CONTINUE

Over the decades, there have been many theories as to what happened to the Peking Man fossils. Some speculate they were spirted away to the Philippines, while others believe they were lost at sea when the American ship carrying them was sunk by Japanese bombers. Another speculation pressed that they successfully arrived in the US and the crates remain hidden in a long-forgotten corner of military warehouse.

Though the original fossils were lost to history, their impact on our understanding of human evolution endures. Scientists continue to study other hominid remains uncovered at Zhoukoudian to piece together clues about our shared ancestry and heritage.

THE SCIENCE

CONTINUES

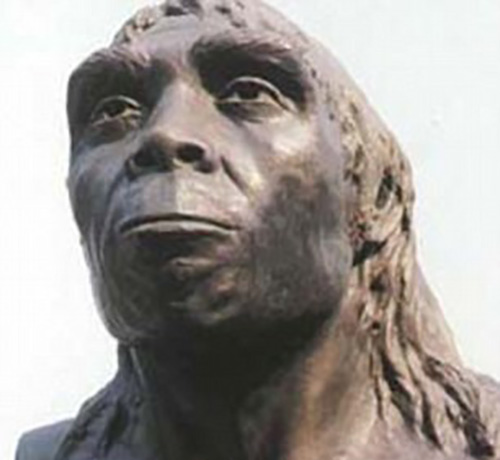

With advances in technology, researchers have been able to reconstruct the appearance and behavior of Peking Man with remarkable precision. From facial reconstructions to virtual simulations, these efforts have breathed new life into these ancient beings, offering fresh insights into their lives and times.

Wherever or not the fossils still exist, the tale of the Peking Man fossils is a testament to the resilience of scientific inquiry in the face of adversity. From their discovery amidst the deep caves of Zhoukoudian to their mysterious disappearance during World War II, these ancient bones have left an indelible mark on our understanding of human evolution. Though their fate may remain a mystery, their legacy continues to drive our quest to understand our origins and place in the natural world.

Further Reading